in the clouds

My experience earning the instrument rating

Beyond the private pilot rating, the instrument rating is the next major milestone in many pilot’s journey. It is a step from amateur flying into a more “professional” world, as you get to participate fully in the National Airspace System. You can fly in clouds, above 18,000 feet (if your airplane allows), and with the same priority (and procedures) as the commercial airliners.

I started my IFR training in the Spring of 2017, in a Redbird FMX at the (now closed) Advanced Flyers club in Palo Alto, CA. I continued my training at the New Century AirCenter in Gardner, KS during my summer internship at Garmin - even passing the written exam on the day of the ‘Great American Eclipse.’ After that, flying took the backseat to my coursework, so I did not resume my IFR training until the Spring of 2020 at the Doylestown airport. I re-passed the written exam that summer, but was not able to take the checkride due to the quality of the rental aircraft. After finding a wonderful airplane in the Princeton Flying Club, and getting my skills back to checkride standards, I finally took (and passed) the instrument checkride on April 23, 2023 - after 6 years of on-and-off work!

IFR Training

I found instrument training challenging, yet extremely rewarding. During a precision instrument approach, focusing on the needles (and other instruments) puts me in a state of total concentration and flow. Flying instrument requires a good mix of flying skill as well as knowledge of a complex airspace system. Here are my tips for training for the instrument rating (or currency):

- Sheppard Air is a fantastic way to prep for the written exam. “Sometimes, it’s not about what’s right, but rather what they’re marking as correct!”

- If you don’t already, subscribe to the Aviation News Talk Podcast. Super-CFI Max Trescott puts out amazing content that is regularly geared towards instrument flying. I especially recommend episodes 129 (mock instrument checkride), 242 (CFII mock checkride), and 269 (foreflight tips for checkrides). Each of these episodes are interviews with DPEs. Beyond instrument, this show has educated me (and countless others) immensely in aviation safety topics.

- Get experience (with your CFII) filing IFR and flying in actual instrument conditions. I was lucky enough to fly extensively with an amazing CFII, Connor Quinn, who had me regularly file IFR and fly in actual during training. Nothing replaces the intensity and task-saturation of calling approach while entering the clouds just after takeoff. And no foggles come close to the first time you fly into a cloud and lose all sense of spatial awareness. It is an incredibly humbling, motivating, and empowering experience.

- Listen to LiveATC! Early in my training, I had trouble following the rapid-fire radio calls and clearances from approach during practice approaches. “Skyhawk 99338 2 miles west of HASIS turn right heading 090 maintain 3000 until established on the localizer cleared ILS 13 approach into Allentown.” It helped immensely to listen to nearby approach on LiveATC to find structure in the radio calls and practice read-backs. It also helped to write out example radio calls and replies, acting out the part of ATC and pilot.

- Be, and fly with, safety pilot. Outside of flying with your CFII, take a pilot friend (safety pilot) and fly practice approaches in simulated instrument conditions. Flying with a safety pilot can be more challenging, as your instructor sometimes “continues teaching” (instead of letting you make mistakes). It is empowering to fly the approaches by yourself. Bonus points if your safety pilot is IFR rated and can offer tips. It’s also useful to fly as safety pilot for someone else getting their 6HITS, and seeing their strategy!

IFR Checkride

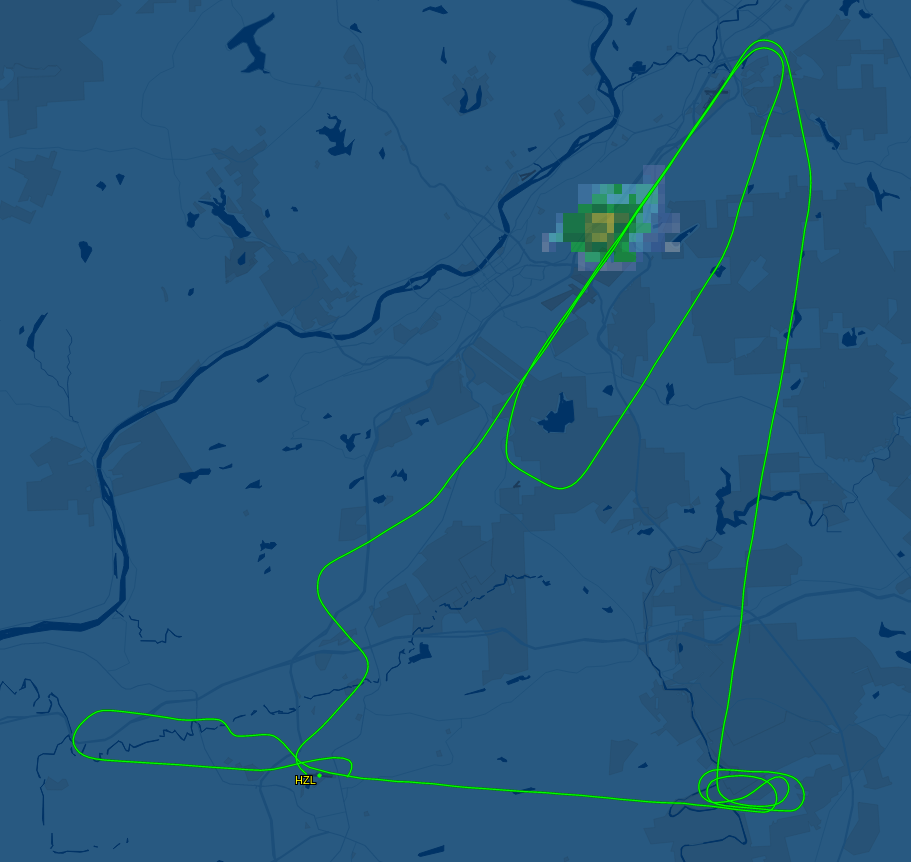

I conducted my checkride on April 23, 2023 with DPE Byron Hamby at KHZL (Hazleton Regional Airport).

Oral Exam

For my oral exam, I was assigned to plan a cross country flight plan from Hazleton to Rutland, VT (KRUT). The forecast along my filed route and altitude was above the freezing level but below the overcast layer.

Here is a subset of the questions I was asked in my oral exam.

- What currency requirements do you need to act as PIC under IFR?

- In the forecast conditions, what is your decision regarding the flight plan to KRUT?

- At your filed route and altitude (clear of clouds but above the freezing level), could you pick up icing?

- What would you do if ATC assigns you to climb into the overcast layer?

- If you enter the clouds, what are you looking out for?

- Describe the types of structural icing and the conditions in which they occur.

- Which structures on the aircraft are most susceptible to icing?

- What are the consequences of picking up icing on the tailplane?

- How would you fly differently (cruise, approach, landing) assuming that you have ice on your tailplane?

- You notice that you are picking up rime on your leading edge. What do you do?

- Which approaches are available at KRUT?

- Why is there both an ILS Y and an ILS Z? (Hint: There is a major item here that you must pick up on.)

- Between the ILS Y and an ILS Z, which would you choose and why?

- What is the standard expected climb performance? (ft/nm)

- What is your aircraft’s expected climb performance? (ft/nm) How would you calculate it?

- What instruments do you have in your aircraft (steam gauge / vacuum / glass)?

- What systems would fail (and how) if your aircraft’s battery failed?

- What systems would fail (and how) if your aircraft’s alternator failed?

Practical Exam

At the end of my oral exam, Byron casually briefed the approaches of my practical exam. I made sure to take notes to review the approaches during my break / preflight. He gave me a sample IFR clearance to Wilkes Barre (KAVP). The clearance read (roughly) as follows:

November XXXXX, you are cleared to the Alpha-Victor-Papa airport via Lima-Victor-Zulu then direct as filed. Climb and maintain four thousand, expect five thousand one zero minutes after departure, departure frequency is one two six point three, squawk one two zero zero.

He noted that I would take off and initiate my climb, go under the hood at 500 feet, call Wilkes-Barre Approach and request the ILS 22, go missed, re-fly the ILS 22, go missed again, request the LOC 28 approach at KHZL, perform the procedure turn / holding maneuvers at WEISS, then (after holding) fly the LOC 28 approach at KHZL, land, takeoff, conduct unusual attitude recovery, and then fly the RNAV 10 (partial panel - loss of attitude), circle to 28.

I reviewed the approaches during a brief break, then Byron watched as I pre-flighted the airplane for IFR conditions. I checked the weather and noted that the wind (slightly) favored RWY 4 at KAVP, so I took a quick look at their approaches as well. After thoroughly following the checklist and a careful taxi to 28, we departed and the checkride was underway!

As soon as we took off, I began to feel task saturation. Foggles on, climbing turn to LVZ. I was perplexed by the KAVP ATIS frequency of 111.6, which I could not dial into COM2. It took me a second to realize that it was the LVZ VOR frequency, and that I should listen to ATIS over the NAV radio. (This is something I do not recall demonstrating during training.) The LVZ frequency is indeed underlined on the charts. I got ATIS, and noted that ILS 4 was in use. I called Wilkes-Barre Approach to request a practice approach, and was immediately vectored to join the localizer for RWY 4.

At this time, I was fully task saturated and even felt that I was falling behind the airplane. The approach controller was speaking very quickly, I was loading a new approach, I was not entirely sure where we were, I hadn’t had time to brief the approach, and suddenly I was cleared for the approach. I started to verbalize my task saturation, and that I wasn’t seeing the expected indications for the localizer on my HSI. I suddenly realized that I hadn’t switched the Garmin GI-275 from GPS to LOC mode, so I wasn’t picking up the localizer frequency dialed into my NAV 1. (I typically load the approaches using GPS for increased situational awareness, but I must remember to switch to the localizer frequency.)

After that, the needles came alive and I was able to calm down and continue to fly and brief the approach. That moment was definitely the closest I came to failing the exam, as I was highly saturated and falling behind the airplane. What had happened is that, instead of getting the ILS 22 approaches (as expected), which would have given me 10 minutes to fly to the north side of the airport and become situated, I was given the ILS 04 approach which started almost immediately after takeoff. In our debrief, Byron pointed out that I could have requested vectors from the approach controller to give me a few minutes to get situated before starting the approach. It was a valuable lesson in task saturation; I genuinely felt uncomfortable as I fell behind the airplane. It is easy to forget during a checkride that we are also being evaluated in our judgement when things aren’t going our way; it is always better to go missed (or go around) instead of forcing an unstabilized landing. It is one of the ways we can save our checkride! In the end, I was lucky that I could problem-solve my mistakes quickly enough to continue (and pass) the checkride.